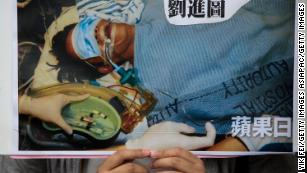

Protesters display placards during a rally to support press freedom in Hong Kong on March 2, 2014.

Keeping quiet

Under

Hong Kong's de facto constitution, the Basic Law, residents are

guaranteed "freedom of speech, of the press and of publication," rights

that are not granted, or protected in mainland China.

While

this means there is little top-down control of media in Hong Kong,

self-censorship within the local press has been widely reported, both by

front-line reporters and editors who have left publications they felt

were unwilling to stand up to the government or corporate pressure.

One

of the best descriptions of self-censorship, and its pernicious power

which sometimes outstrips that of more aggressive control, comes from China scholar Perry Link.

"(The)

government's censorial authority in recent times has resembled not so

much a man-eating tiger or fire-snorting dragon as a giant anaconda

coiled in an overhead chandelier," Link wrote about academic

self-censorship in China.

"Normally

the great snake doesn't move. It doesn't have to. It feels no need to

be clear about its prohibitions. Its constant silent message is 'You

yourself decide,' after which, more often than not, everyone in its

shadow makes his or her large and small adjustments -- all quite

'naturally'."

While mainland China

has a massive formal censorship apparatus, controlling all aspects of

society from movies and music, to the Internet and book publishing, much

of what affects people on a day to day level is closer to

self-censorship.

Social media

firms, for example, employ hundreds of censors to police what their

users say, but for the most part, they do so without guidance or

direction from the central government, second guessing what their

bosses, and by extension the Communist Party's official censors will

disapprove of.

In this context,

self-censorship becomes more effective the more unclear the boundaries,

and the greater the repercussions for potentially stepping across them.

This

could be seen in Hong Kong in the wake of the attack on Lau, as the

chance of a violent response to a story suddenly seemed a real

possibility to many reporters, compounding existing fears about the

"wrong" story costing the journalist their job or resulting in costly

legal proceedings.

For over a

decade, however, even as warnings grew about self-censorship by Hong

Kong reporters, and media ownership was consolidated by a few

China-friendly businesspeople, the foreign press has largely operated

unfettered, a stark contrast to China, where international reporters

regularly harassed, ejected from the country, and their local colleagues

arrested and jailed.

That all changed this year.

Action reaction

The

Foreign Correspondents' Club of Hong Kong is positioned half way up a

hill on a busy, windy road with narrow pavements and multiple lanes in

the city's Central district.

It's

not a good venue to protest outside of, and yet, in August several dozen

people squeezed themselves into police cordoned-off areas opposite and

next to the club, bearing banners accusing the elite institution of

being involved in a "conspiracy to split Hong Kong from China."

Inside, the focus of the protests, Andy Chan, sat looking calm and composed as he prepared to give a speech arguing for the city's independence.

He chatted casually with FCC staff, and laughed when fire department

officials rushed into the building carrying axes in response to an

apparent hoax call.

Within days of

the event taking place, Chan's Hong Kong National Party was officially

banned under public security laws, the first time they had ever been

used to go after a political organization. The FCC itself, meanwhile,

was facing a storm of publicity amid calls for it to lose the lease to

its property and potentially even its license to operate.

By

October, those fears appeared misguided, until Victor Mallet, an editor

at the Financial Times who had hosted Chan in his capacity as

acting-FCC President, put in for a routine visa renewal.

Compared

to China and many other countries in the region (including ones which

boast about being democracies), Hong Kong is an incredibly easy place to

get a journalist visa, but Mallet had his refused, an almost unprecedented move the government has yet to explain but nearly everyone else has connected to the Chan talk.

While

the local government has consistently denied that Mallet's ejection was

anything to do with press freedom, the failure to provide an alternate

explanation, as well as the facts of the case, have left most to draw

their own conclusions.

"We ... are

deeply concerned that with this action, taken with no stated or

apparent legal basis, Hong Kong's special place as a bastion of free

expression and a free press has been eroded," 17 former presidents of

the FCC wrote in an open letter to Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam after

Mallet was denied entry to the city as a visitor on November 8.

New normal

While

reporters working in mainland China are obviously subject to the

pressures and concerns that can lead to self-censorship -- fear of

violence, fear of being ejected from the country or even jailed -- there

is an additional factor in Hong Kong, in that the city has long been a

place where many expats, including foreign reporters, are more like

immigrants, getting permanent residency and raising their children,

rather than moving on after a few years.

Being

ejected from a country one never had any intention of living in can,

though most journalists would not admit it, be a boon to career

prospects, significantly building the reporter's profile and reputation.

But being forced to leave somewhere you intended to raise your family

and settle down can be devastating, and questions naturally arise over

whether any given story, or event, or interview, is worth that?

Recent weeks have seen two incidents which appear from the outside to be clear cut cases of self-censorship.

The specter of the attack on Lau, as well as the 2015 disappearance of several Hong Kong booksellers, was raised on November 2, when the organizers of a show by Chinese dissident artist Badiucao canceled the event, a day before it was due to take place, alleging "threats made by the Chinese authorities relating to the artist."

This

was followed by the cancellation of a talk by another Chinese exile,

novelist Ma Jian, at Tai Kwun, an art space which has received

government funding, as part of a series of events connected to the Hong

Kong International Literary Festival.

In

a statement, the Director of Tai Kwun, Timothy Calnin, said organizers

"do not want Tai Kwun to become a platform to promote the political

interests of any individual."

"The

cancellation appears to be at the very least an act of self-censorship,

which would add to a growing list of incidents of suppression of free

expression in Hong Kong," said Jason Y. Ng, president of PEN Hong Kong, a

pro-free speech organization.

"It

is all the more jarring that the decision was made by a publicly funded

venue that claims to celebrate and support the arts and creativity,"

added Ng.

The

self-censorship charge appeared to be confirmed when Tai Kwun abruptly

reversed its decision and agreed to host Ma after all.

"Ma

has made public statements which clarify that his appearances in Hong

Kong are as a novelist and that he has no intention to use Tai Kwun as a

platform to promote his personal political interests," Calnin said in a

statement.

Over all of this --

Mallet's visa refusal, Badiucao's cancelled show, Andy Chan's banned

party, and all the protests and demonstrations they inspired -- hangs a

long delayed anti-sedition provision contained within the Basic Law, the

city's de facto constitution.

Article

23 of Basic Law instructs the local government to "enact laws on its

own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion

against the Central People's Government ... and to prohibit political

organizations or bodies of the region from establishing ties with

foreign political organizations or bodies."

Attempts

to implement the law in 2003 sparked massive street protests which

eventually saw it shelved, but it has remained a priority of the central

government and current leader Carrie Lam has vowed to create "suitable

conditions" for passing the law, though she has not outlined any

timetable.

While the Hong Kong

government has shown it is not lacking in powers to go after protesters

or dampen expression, Article 23 would massively expand the amount of

forbidden topics in a city already nervous about its freedoms, and

possibly even end its role as a hub for international media in Asia.

Speaking to reporters at the Tai Kwun event, Ma Jian said people nevertheless need to "have the courage to break" through self-censorship.

"The

freedom to speak is the basis of our civilization," he added. "We have

to safeguard our freedom of expression. We have to safeguard our

civilization."

![Death knell' of press freedom in Hong Kong has been a long time coming]() Reviewed by Unknown

on

12:39 PM

Rating:

Reviewed by Unknown

on

12:39 PM

Rating:

No comments: